Himachal Pradesh

- Oct 11, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Oct 31, 2025

Following India's independence in 1947, Himachal Pradesh was divided into the East Punjab hill states, two segments of the East Punjab States, and the princely state of Bilaspur. This story is about the politics behind unifying these four regions.

Following India's independence in 1947, the present state of Himachal Pradesh existed in four parts: (i) 28 East Punjab hill states (present-day Himachal Pradesh), (ii) two contiguous parts of the East Punjab States, and (iii) Bilaspur. Each had distinct political relationships with British India and differing levels of administrative evolution.

The East Punjab Hill States were a collection of small princely states nestled in the western Himalayas, many of which had remained semi-autonomous under British suzerainty. Despite their size, they were culturally rich and politically active, with unique administrative systems. These included Chamba, Mandi, Suket, Sirmaur, Bashahr (now Kinnaur), and others. Many of whom had experienced popular mobilisation in the late colonial period (Census of India, 1941).

These states included long-standing Rajput principalities with varying political systems, while the two parts of the East Punjab States (Patiala and East Punjab States Union, together called PEPSU) had their trajectory of merger and consolidation. Bilaspur’s direct control by the Punjab States Agency further separated its political fate from its geographic neighbours. This fragmentation reflected the administrative patchwork inherited from colonial governance and highlighted the challenges of integrating such a mosaic into a singular political identity.

In March 1948, the East Punjab Hill States signed agreements to cede authority and governance to India, resulting in the creation of Himachal Pradesh. However, it continued to exist as two non-contiguous territories, separated by East Punjab. It was designated a chief commissioner’s province. Despite demands for Punjabi Suba, an immediate merger with the province was seen as impractical by the States Ministry. They preferred not to mix the residents of the hills and plains into a common administrative system (Government of India, 1950).

The creation of Himachal Pradesh as a political entity was not accompanied by administrative coherence. The hill states were geographically dispersed and lacked territorial contiguity. The new unit was split by intervening territories that remained part of East Punjab, creating logistical and governance challenges.

Meanwhile, in the broader Punjab region, the Punjabi Suba movement, led by the Shiromani Akali Dal, called for a separate Punjabi-speaking state (Singh, 1945). The States Ministry, led by Sardar Patel and V.P. Menon, was cautious about accommodating regional demands in the volatile post-Independence climate. Merging the culturally distinct and topographically challenging hill regions with the plains of Punjab risked administrative and political instability. Hence, Himachal Pradesh was retained as a separate unit, though administratively isolated (Singh, 2019).

Bilaspur later joined the Union but was not immediately integrated into Himachal. While geographically aligned with the other hill states, Bilaspur had a unique status. At Independence, it was under the Punjab States Agency and was excluded from the 1948 merger (Government of Himachal Pradesh, n.d.). Its strategic importance stemmed from the Bhakra Nangal Dam project – an ambitious hydropower and irrigation initiative vital to India’s post-independence development. Bilaspur was kept under direct central control to ensure progress on the dam (Mamgain, 1975).

On 12 October 1948, the Raja of Bilaspur, Anand Chand, was appointed chief commissioner. As per the Merger Agreement, he was granted a privy purse of ₹70,000—greater than that of the other East Punjab Hill States. His appointment was unusual, as most former princely rulers were excluded from governance after accession. The generous settlement reflected Bilaspur’s strategic importance. Allowing the Raja a quasi-administrative role ensured the smooth implementation of the dam and helped pacify local elites (Rajya Sabha, n.d.).

As a chief commissioner’s province, Himachal Pradesh was directly governed by the central government through an appointed commissioner, limiting its autonomy. This arrangement reflected the Centre’s cautious approach to integrating peripheral regions without prematurely granting statehood or legislative powers. The decision not to merge Himachal with East Punjab was not just logistical—it acknowledged the cultural distinctiveness of the hill people and the risks of forced integration (SRC, 1955).

In 1950, Himachal became a Part C state under the new Constitution, governed by a lieutenant governor appointed by the President. Though a step forward, this did not provide full legislative authority. The demand for statehood persisted through the 1950s, led by hill leaders seeking political autonomy and a development focus (Constitution of India, 1950).

In 1954, Bilaspur was merged into Himachal Pradesh, fulfilling a long-standing demand and improving territorial coherence (Constitution of India, 1950). Further progress came in 1956, when the States Reorganisation Commission (SRC) proposed integrating additional hill areas. However, due to its small population and economic backwardness, Himachal was not granted full statehood. Instead, it became a Union Territory, though with an elected Legislative Assembly from 1963 (SRC, 1955). It became the first step towards Himachal's statehood.

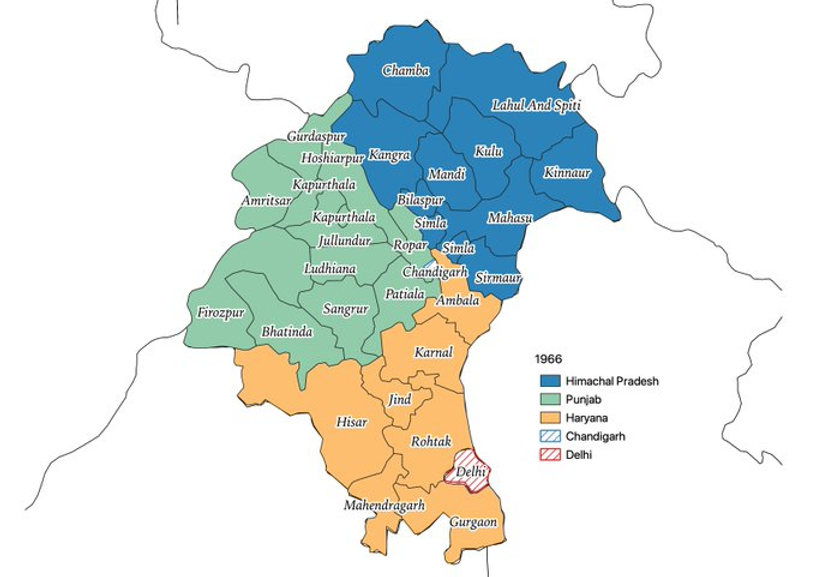

In 1966, while the Punjab Reorganisation Bill was being debated in Parliament, the matter of Himachal’s statehood was raised. In July 1967, the Himachal Pradesh legislative assembly adopted a unanimous resolution calling for statehood as ‘a just demand of the Himachalis. The final milestone came on 25 January 1971, when Parliament passed the Himachal Pradesh State Act, making it the 18th state of the Indian Union (Parliament of India, 1970). This followed decades of incremental change, public agitation, and institutional lobbying. Dr. Y.S. Parmar, widely regarded as the architect of modern Himachal, became the first Chief Minister of the new state.

The formation of Himachal Pradesh, therefore, helped bring focused governance to one of India’s most administratively challenging terrains.

References

Census of India (1941). "Census of India, 1941: Volume VI – Punjab". Government of India.

Constitution of India (1950).

Government of Himachal Pradesh (n.d.). District Bilaspur.

Government of India (1950). White Paper on Indian States. New Delhi: Ministry of States.

Mamgain, M.D. (1975). Himachal Pradesh District Gazetteers: Bilaspur.

Parliament of India (1970). The State of Himachal Pradesh Act 1970.

Rajya Sabha (n.d.). Rajya Sabha Members Biographical Sketches 1952-2003.

Singh, R. (2019). Himachal’s quest for identity. The Tribune.

Singh, T. (1945). Meri Yaad.

States Reorganisation Commission (1955). Report of the States Reorganisation Commission. Government of India.

Comments