Lakshadweep

- indiastatestories

- Oct 11, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Oct 31, 2025

The Lakshadweep Islands, located in the Arabian Sea, consist of thirty-six islands of three subgroups: Aminidivi, Laccadive, and Minicoy.

The island’s first settlement is said to have been during the reign of the Kerala Chera King Cheraman Perumal – he once disappeared, following which a search party for him ended up on the Amini island. In the 10th century, the Kadambaris of Goa captured Kavaratti; after this, these islands were part of the Chola dynasty during the medieval period and later, the Kingdom of Kannur (Tripati, 1999; Nilakanta, 1955). The region was then taken over by the Muslim house of Arakkal, with the Amindivi Islands being ceded to Tipu Sultan.

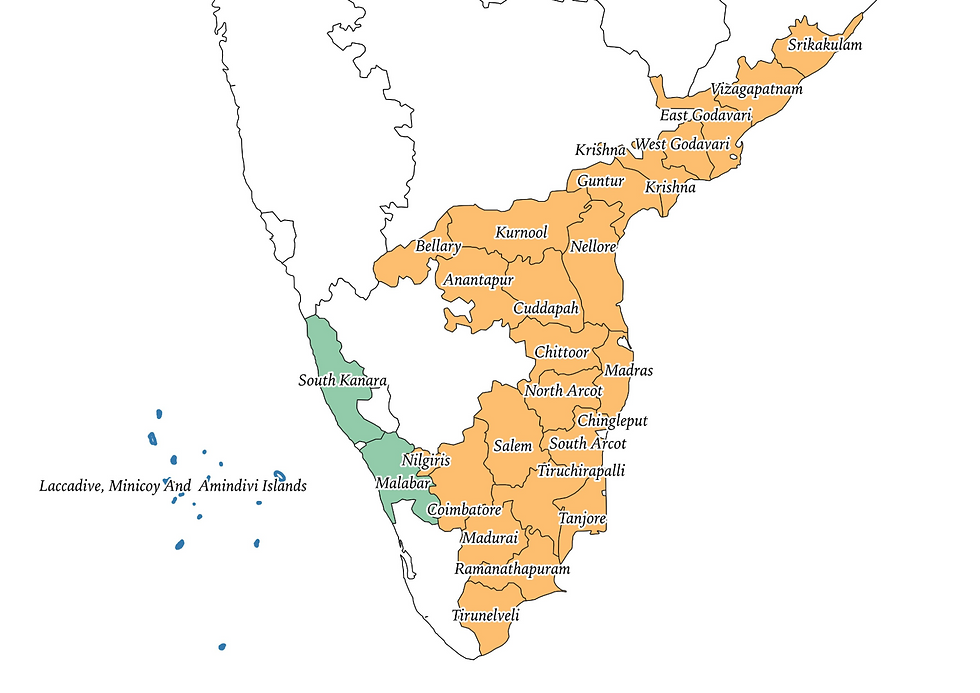

Following the fourth Anglo-Mysore War in 1799, the Amindivi Islands were annexed by the British East India Company and administered from Mangalore – the rest of the islands were to be under the House of Arakkal, who paid a tribute to the British (Logan, 2010; Singh, 2014). The British later claimed that these tributes were unpaid and annexed the rest of the islands too, clubbing them under the Madras Presidency. Therefore, the northern Amindivi subgroup was administered from South Canara, while Laccadive and Minicoy were administered from Madras’ Malabar (Logan, 2010).

When India gained independence in 1947, the islands were transferred to India and continued to be administered by South Canara and Malabar under the newly formed Madras State. The turning point in its evolution came in 1953 via the States Reorganisation Commission (SRC). In its 1955 report, the SRC recommended merging South Canara with the Mysore State and the Malabar district with Kerala. To simplify administration, the commission additionally suggested that Kerala govern the rest of the islands as well (Government of India, 1955).

However, the central government decided to instead convert the islands into a Union Territory and thus place them directly under the President of India. This was primarily due to two factors: (i) long-term naval interests in the region, as articulated by K.M. Panikkar at the time of India’s independence, and (ii) concerns over a possible communist regime in Kerala and its implications for the islands (Panikkar, 1951).

In 1956, with the enactment of the States Reorganisation Act, the union territory of Laccadive, Minicoy, and Amindivi Islands came into being (Government of India, 1956). Later, as relations with the islands improved, the Administrator’s Advisory Council suggested renaming the islands as Lakshadweep. This change was formalised with the passing of the Laccadive, Minicoy, and Amindivi Islands (Alteration of Name) Act on 26 August 1973.

Modern administration

The creation of the Union Territory status helped Lakshadweep retain a distinct administrative identity, separate from the states on the mainland. Despite their small sizes and remoteness, the islands gradually became politically significant due to their strategic maritime position, and they began receiving tourist attention for their rich biodiversity and unique culture.

The population of Lakshadweep developed its own pace of political consciousness. The Lakshadweep Panchayati Regulation Act of 1994 thoroughly restructured the islands’ governance (Government of India, 1994). Each island now has a Dweep Panchayat with 79 members each, and there is a singular District Panchayat with one member for each island. This has granted more voice to the local population in administrative affairs, even as key powers remain concentrated in the hands of the President-appointed Administrator. The Kerala High Court oversees the activities of the local courts.

Over time, the islands have witnessed growing political participation. Lakshadweep only has one seat in the Parliament – its first MP after independence was P.M. Sayeed, a Congress leader who represented the territory for ten consecutive terms from 1967 to 2004. He played a crucial role in representing the islands on the mainstream, national stage and championed development causes for his constituency (ToI, 2005).

In recent years, there has been an increasing clash between national agendas and local resistance. Controversies erupted in 2021 when new administrative reforms were proposed by the then-Administrator Praful Khoda Patel. These included changes to land use regulations, restrictions on beef consumption, increased policing powers, and a proposed Prevention of Anti-Social Activities Regulation (commonly called the Goonda Act). The measures sparked widespread protests both in Lakshadweep and on the mainland, with critics arguing that the reforms disregarded local culture and ecological sensitivities. Various political parties and civil society organisations united for this cause. The episode highlighted the limitations of top-down administrative models and reaffirmed the need for participatory governance in Union Territories (Mumthas, 2021).

Despite such tensions, development efforts in Lakshadweep have continued in sectors such as renewable energy, marine conservation, and tourism. The central government has also initiated projects to improve air and sea connectivity, healthcare infrastructure, and internet access. However, these efforts must carefully balance ecological preservation with economic development, given that the islands are highly vulnerable to climate change, rising sea levels, and coral bleaching.

As India navigates the 21st century, Lakshadweep's future will depend on how well policy decisions respect the cultural, ecological, and political specificities of this fragile archipelago. Strengthening local governance, ensuring sustainable development, and safeguarding civil liberties must be the government’s foci.

References

Government of India (1956). States Reorganisation Act (1956).

Ministry of Panchayati Raj. (1994). The Lakshadweep Panchayats Regulation, 1994. Government of India.

Government of India (2003). 20 Year Perspective Plan for Tourism Development in Lakshadweep Islands. Department of Tourism.

Logan, William (2010). Malabar Manual (Volume-I). Asian Educational Services, New Delhi.

Mumthas, M. (2021). Lakshadweep and the Land Question: Historicising the Present Crisis. Economic and Political Weekly.

Nilakanta, S. (1955). The Cholas (2nd ed.). G. S. Press, Chennai.

Panikkar, K.M. (1951). India and the Indian Ocean. G. Allen & Unwin, London.

Singh, A.P. (2014). Anthropology of Small Islands: The Case of Lakshadweep Islands of India. Anthropological Bulletin, 3(2), pp. 20-28.

States Reorganisation Commission (1955). Report of the States Reorganisation Commission. Government of India.

Tripati, S. (1999). Marine Investigations in the Lakshadweep Islands. Cambridge University Press.

Comments