How is a new state formed?

- indiastatestories

- Jan 22, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 17, 2025

States are not sovereign in India

None of the Indian states were originally sovereign entities; they did not exist as independent units before joining the Indian Union. Part A states (Governors' provinces) were administered centrally until 1937, with limited devolution starting from 1919. Under the 1935 Act, certain powers were assigned to provinces, but the Governors retained significant authority under the control of the Governor-General. Chief Commissioners' provinces were recognized as federal units but were still governed centrally. Former princely states claimed some sovereignty but were under British paramountcy, limiting their control over both external and internal matters. The rulers of these princely states surrendered any remaining sovereignty to India before the Constitution was established.

In the years immediately following independence, India’s federal system largely retained the territorial administrative structure established under British rule. This structure reflected the historical patterns of colonial expansion and the arrangements negotiated with various local rulers. The first post-independence map of India preserved the boundaries of the former British Indian provinces with minimal changes, except for the integration of princely state territories.

Unlike the American colonies or Swiss Cantons, no Indian state was independent before forming a federal union. The Indian Constituent Assembly was free to create a constitution that suited India, with no binding commitments from previous structures. Indian Federalism is described as quasi-federal with a strong center, and the Union ‘holds together’ the states. Unlike the U.S., where both the Union and individual states are considered indestructible, in India, only the Union is indestructible, and individual states can be altered or redefined (Source: SRC Report 1955).

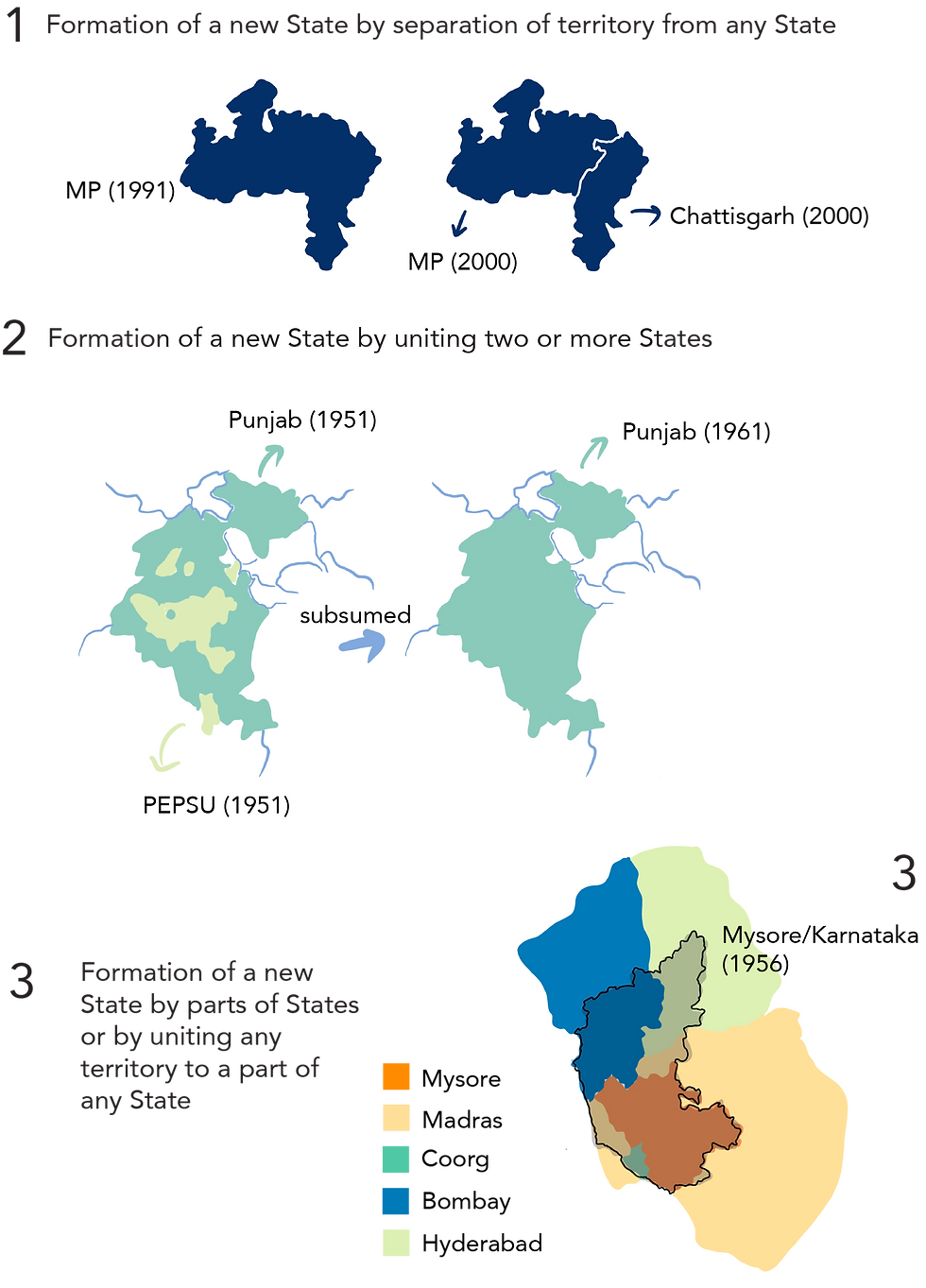

The Constitution explicitly provided the central government with the authority to admit or create new states through Articles 2 and 3. The creation of new states was made a firm prerogative of the Union government. Under Article 3, Parliament, by a simple majority, can enact laws to form a new state by separating territory from an existing state, merging two or more states or parts thereof, or integrating new territories into an existing state. Parliament can also increase or decrease the area of any state, alter its boundaries, or change its name as it sees fit (Indian Constitution, 1950, Tillin, 2013, Tillin, 2019). Importantly, the creation or alteration of states does not require a constitutional amendment (except for minor revisions to the Schedules concerning states) nor the consent of the affected states’ legislative assemblies.

Indian Constitution and the formation of States

Article 1: Name and territory of the Union

India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States.

The States and the territories thereof shall be as specified in the First Schedule.

The territory of India shall comprise-(a)The territories of the States;(b) the Union territories specified in the First Schedule; and (c) such other territories may be acquired.

Article 2: Admission or establishment of new States

Parliament may by law admit into the Union, or establish, new States on such terms and conditions, as it thinks fit.

Article 3: Formation of new States and alteration of areas, boundaries or names of existing States

Parliament may by law-

Form a new State by separation of territory from any State or by uniting two or more States or parts of States or by uniting any territory to a part of any State;

increase the area of any State;

diminish the area of any State;

alter the boundaries of any State;

alter the name of any State;

Provided that no Bill for the purpose shall be introduced in either House of Parliament except on the recommendation of the President and unless, where the proposal contained in the Bill affects the area, boundaries, or name of any of the States, the Bill has been referred by the President to the Legislature of that State for expressing its views thereon within such period as may be specified in the reference or within such further period as the President may allow and the period so specified or allowed has expired.

In this article, in clauses (a) to (e), "State" includes a Union territory, but in the proviso, "State" does not include a Union territory. The power conferred on Parliament by clause (a) includes the power to form a new State or Union territory by uniting a part of any State or Union territory to any other State or Union territory.

While language has been a powerful basis for statehood demands, it is not the sole determinant. The pursuit of economic advancement, social status, and political power by specific elites also plays a role in the mobilisation for new states. The central government also considers administrative, financial, and political factors, alongside linguistic homogeneity, although a 'balanced approach' was advocated where linguistic homogeneity was important but not exclusive. (Tillin, 2013)

Tillin in her work Remapping India illustrates that, post-independence, state design initially focused on integrating princely states while largely maintaining British provincial structures. Despite the significance of language in shaping nationalist sentiments, the initial approach favoured national consolidation over linguistic homogeneity. However, strong regional demands led to the linguistic reorganisation of states in the 1950s and 1960s, particularly in South and West India. The Hindi-speaking heartland largely retained its large state structures (barring Madhya Pradesh) due to strategic considerations about national unity and the influence of existing political power dynamics. The constitutional framework under Articles 2 and 3 provided the central government with significant authority in shaping the internal boundaries of the nation, a power that has been exercised and debated throughout India's post-independence history.

While the formal process of forming a new state in India rests with the central government and Parliament, the impetus for such formations often originates from long-standing regional aspirations articulated through social movements. The alignment and interaction of these movements with political parties, each with their own strategies and goals, play a critical role in bringing the demand for statehood to the forefront of the political agenda, ultimately influencing the central government's decision to enact the necessary legal changes. The creation of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Uttarakhand exemplifies this dynamic, marking a shift towards the recognition of non-linguistic bases for statehood in India. (Tillin, 2011 )

The culmination of these processes eventually lead to the initiation of the legislative process in the parliament. The central government introduces a bill in parliament for the formation of a new state or an alteration of existing state boundaries. The bill typically requires recommendation from the president before being introduced. Parliament then debates and votes on the bill in both the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha. Generally, a majority is required for passing such a bill. Once the bill is passed in both the parliaments, it is presented to the president of india for their assessment. Upon presidential assessment, the bill becomes an Act and the new state is formally created on the notified date (Indian Federalism -Tillin, 2019).

Comments